Theory

Prediction of frequencies and probabilities of transition between energy levels of muonic atoms

X-Ray Spectroscopy with negative muons

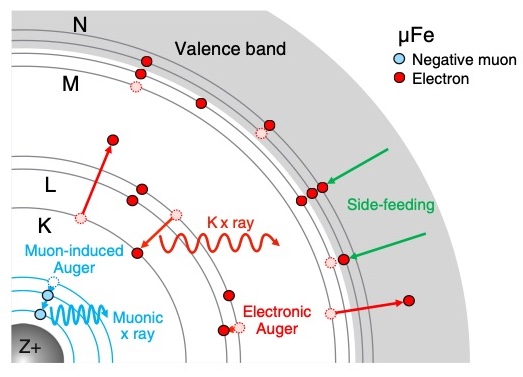

While positive muons can be used as magnetic probes acting as if they were light protons, negative muons have wholly different uses due to behaving in matter more as if they were heavy electrons. Negative muons possess the same charge and spin as electrons, and so will form bound states with nuclei that are known as muonic atoms. These atoms possess peculiar properties due to the heavier mass of the muon:

the muon orbitals around the nucleus are much smaller and denser than the electronic ones, meaning that the muon tends to be rather insensitive to the presence of electrons - as it is closer to the nucleus than any of them (See Figure 1);

for the same reason, the muon orbitals can overlap significantly with the atomic nucleus, and their energy is affected by the shape of its charge distribution;

the muon orbitals have much higher binding energies, which means they can also be treated only with a relativistic theory. In classical terms, you could say the muons are ‘orbiting’ the nucleus at speeds close to that of light.

Figure 1: Schematic drawing of the muon cascade process and the electron configuration evolution in a muonic iron atom within Fe metal. Side feeding and electron refilling, via radiative decay or electronic Auger decay, fill the electron holes. It is assumed that the number of 4s electrons is a constant during the cascade because of rapid N-shell side feeding. Figure taken from T. Okumura et. al. PHYSICAL REVIEW LETTERS 127, 053001 (2021).

The consequence of these facts is that when cascading on a nucleus to form a muonic atom, muons will shed their energy in the form of highly energetic X-Ray photons, and the specific energies of these photons will be tied to the transitions between levels that are unique for each element. For this reason, muons can be an excellent probe for non-destructive elemental analysis. The exact characteristic energies for each element can be tabulated by experimental calibration, but they can also be modelled from first principles, by solving the quantum equations to find the orbitals and their energies. However, this is not as simple as applying the usual Schrödinger equation, because the muons orbit the nucleus at relativistic energies and the Dirac equation is necessary; plus, at these energies, the electrostatic potential itself stops being perfectly Coulombic. For these reasons, we have provided a software that easily allows one to perform these calculations by including all necessary details to achieve precision sufficient for the interpretation of experiments.